Rewriting Heartbreak ❤️🩹

- Shannon Goertz

- Oct 2, 2025

- 5 min read

If old memories still upset you, then you can write them down carefully and completely.

I'll tell you a study first was done by this man named James Pennebaker, a couple of studies, and many other people have done similar studies, and Pennebaker wanted to test a Freudian idea, idea derived from Sigmund Freud, that expressing emotion about past trouble was curative, and so he had university students come in and write three days in a row for 15 minutes about the worst thing that ever had happened to them, or to come in for three days and write for 15 minutes about things that had happened that were mundane in the last couple of weeks, and then he tracked them across time, and many people have done studies like this.

He found that people who wrote about negative past experiences were unsettled by it to begin with, unsurprisingly, but six months later, they were doing much better than the control group on a variety of different measures, and because he's a very smart psychologist, he didn't stop there.

He went and looked at their accounts, and he counted the emotion words, and he also counted words that were indicative of understanding or comprehension, and then he used the number of those words to predict how well people did, and what he found was that emotional content didn't predict improvement, but words indicative of understanding did, and that's an extraordinarily interesting finding.

I want to explain, at least in part, why it's so relevant, so then we might talk a little bit about memory, and what memory is, and what it's for.

I’ll tell you a quick story. I had this client I only saw once, back when I was just starting to work as a clinical psychologist. She was about 28 years old and came in to recount a story of being sexually assaulted by her much larger brother. She was very tearful as she told me.

At the end, I asked, “How old were you when this happened?” She said, “I was four.” In my mind, I pictured a four-year-old and perhaps a 15-year-old brother. So I asked, “How old was your brother?” She replied, “Six.”

I thought, Six, eh? (She had grown up under the shadow of that event, and it had contaminated her relationships with men and with her family, as you can imagine.) She still carried a deep fear that she was vulnerable in that way.

I remember reflecting, Four and six, eh? “Have you seen a six-year-old lately?”

She said, “No,” and we talked about that. I said, “You know, when you’re four, a six-year-old is an adult. But when you’re 29, a six-year-old is just a kid. Another way of looking at what happened is that you were two very badly supervised children. Something happened, it triggered you, and it stuck.”

That perspective was a relief to her. I’m not claiming there was anything magical about it, but it was striking. She had continued to see herself as fundamentally vulnerable. She hadn’t updated her memory of being four, or her memory of her brother. When I suggested that they had been two badly supervised children, it reframed the entire episode in a new light.

One of the things that struck me about that case was that she wasn’t really the target of someone specifically malevolent or exploitative. Rather, she was at the center of what often becomes a traumatic experience. What fascinated me was that she walked out of that session with a different memory than the one she walked in with.

That’s strange, because we usually think of the past as fixed. But in this instance, the memory she left with was more accurate than the one she arrived with. And that says something important about what memory is really for.

You know, we tend to think of the world as composed of facts, and that what memory is, is a representation of a set of facts, and there's some truth in that, but what's more true is that memory is part of the whole process of behavioral and cognitive adaptation to the world, and that's much more like drawing a map, because what you really want to know about the world is how to make your way through it in a manner that, well, let's say, isn't catastrophic and is also desirable, and the purpose of your memory is to guide you in making those maps into now and into the future.

Why remember otherwise?

You want to extract from the past information that you can use productively in the future, and so for her, the new memory, let's say, was in some sense more useful to her, because she didn't have to think of herself as a four-year-old at the hands of a malevolent force. It wasn't appropriate for her age and level of maturity. She may still have had personality attributes that might have made her a target for someone malevolent, but she didn't have to think of herself as a four-year-old, a target for someone malevolent, but it wasn't obvious merely as a consequence of having that experience 25 years ago that that was the case, so it needed to be updated.

—by Dr. Jordan Peterson

What we learn from this story, and from James Pennebaker’s research, is that memory isn’t just a fixed record of facts. Memory serves a deeper purpose: to help us update our maps of the world so that we can navigate the present and the future without being trapped by the past. Sometimes, as in the case of Dr. Peterson’s client, a memory that has haunted us for years can be reframed in a more accurate, more useful way — one that loosens its grip and allows us to live differently.

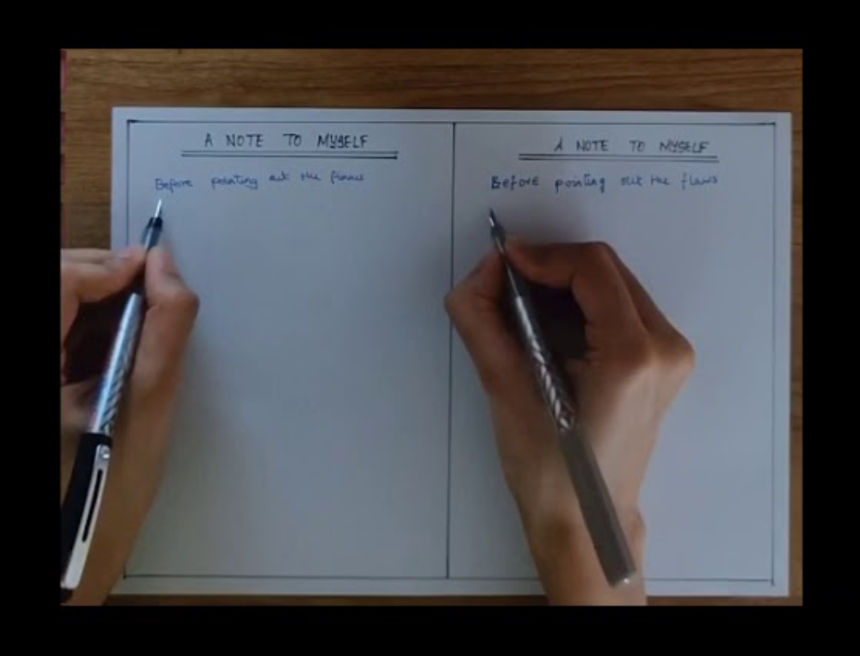

So here’s the practice: if old memories from your divorce or the end of a romantic relationship still upset you, write them down carefully and completely.

Do this for three days in a row, 15 minutes each day.

On Day One, set a timer, write the story straight through, and then put the page away. Do not reread it.

On Day Two, without looking at the first page, write the same story again for 15 minutes.

On Day Three, do the same — no peeking back, just write it fresh.

Then, after a couple of days, sit down and read Page One, Page Two, and Page Three in sequence. Notice the differences.

As Pennebaker found, it’s not simply the emotional outpouring that leads to healing, but the emergence of new words of understanding and comprehension. You’ll often see the story shift, grow clearer, and feel lighter. That is your mind updating itself. That is the power of writing: turning the raw wound of memory into a narrative that can be carried a little easer.

If you don’t feel that it worked?

Then write down all the things that your soon-to-be-ex gave you that another romantic partner cannot give you.

(?)

—Shannon Goertz

Comments